Jalil Muntaqim

Jalil Abdul Muntaqim | |

|---|---|

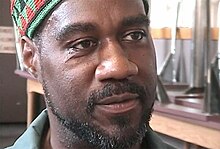

Muntaqim in 2000 | |

| Born | Anthony Jalil Bottom October 18, 1951 Oakland, California, U.S. |

| Occupation | Activist |

| Organization(s) | NAACP, Black Panther Party, Black Liberation Army, Citizen Action of New York Rochester Chapter |

Jalil Abdul Muntaqim (born Anthony Jalil Bottom; October 18, 1951) is a convicted felon, political activist and former member of the Black Panther Party (BPP) and the Black Liberation Army (BLA) who served 49 years in prison for two counts of first-degree murder. In August 1971, he was arrested in California along with Albert “Nuh” Washington and Herman Bell and charged with the killing of two NYPD police officers, Waverly Jones and Joseph A. Piagentini, in New York City on May 21. In 1975, he was convicted on two counts of first-degree murder and sentenced to life imprisonment with possible parole after 22 years. Muntaqim had been the subject of attention for being repeatedly denied parole despite having been eligible since 1993. In June 2020, Muntaqim was reportedly sick with COVID-19.[1] He was released from prison on October 7, 2020, after more than 49 years of incarceration and 11 parole denials.[2][3]

He was portrayed by actor Richard Brooks in the 1985 TV movie Badge of the Assassin.

Early life and political development

[edit]Jalil Abdul Muntaqim was born Anthony Jalil Bottom in Oakland, California and grew up in San Francisco. Drawn to the civil rights activism during the 1960s, Muntaqim joined and began organizing for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) during his teenage years. In high school he played an active role in the Black Student Union and was often recruited to play the voice of and engage in “speak outs” on behalf of the organization. He was also involved in street protests against police brutality.[4]

At the age of 18, he joined the Black Panther Party after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. solidified Muntaqim's beliefs that armed resistance was necessary to combat racism and the oppression of Black individuals in society. While a member of the Black Panther Party, Muntaqim held beliefs which paralleled those of the underground organization the Black Liberation Army, which focused on militant means of obtaining Black national self-determination.[5][6] Its members served as experts in military strategy and were “the essential armed wing of the above-ground political apparatus.”[4]

Arrest and imprisonment

[edit]Muntaqim and Albert “Nuh” Washington were arrested and charged with the May 21, 1971 killings of two NYPD officers, P.O. Joseph Piagentini and P.O. Waverly Jones. Muntaqim and Washington were arrested in San Francisco, reportedly with Jones' revolver in their possession.[7] Police alleged that Muntaqim and Washington had committed the act in retaliation for the killing of George Jackson despite Jackson's death taking place 3 months after the NYPD officers were killed.[8][better source needed] Brothers Francisco and Gabriel Torres were arrested after police were tipped that they had been in contact with Muntaqim and Washington soon after the murders. A few years later in 1973, Herman Bell was arrested for unrelated robberies, but NYPD linked him to a fingerprint reportedly found at the scene. The first trial of the men ended in a hung jury, with the second in 1975 resulting his conviction on two counts of first-degree murder and sentenced to life imprisonment with possible parole after 22 years. The charges against the Torres brothers were thrown out due to lack of evidence, while Muntaqim, Washington and Bell were convicted and sentenced to 25-to-life based on new testimony by Ruben Scott, a police informant in the Black Panther Party.[3] These convictions were part of a larger FBI program known as Operation NEWKILL, which aimed at casting a nationwide dragnet to track down and imprison members of the Black Liberation Army through total cooperation and sharing of information between the FBI and local police departments.[8][9][10]

Muntaqim remained politically active throughout his incarceration, writing theoretical texts[5] as well as organizing with activists both inside and outside prison. While incarcerated, he met fellow Black revolutionaries Jamil Al-Amin and Muhammad Ahmad, who inspired him to convert to Islam and take on the name Jalil Abdul Muntaqim.[11] The English translation of Muntaqim is "avenger." He never made a legal name change. He was involved in the National Prisoners Afrikan Studies Project, an organization that educates inmates on their rights.

In 1976, he founded the National Prisoners Campaign to petition the United Nations to recognize the existence of political prisoners in the United States. During his 49 years of incarceration, Muntaqim and other Black Panthers imprisoned as part of Operation NEWKILL were widely described as political prisoners, including by the National Conference of Black Lawyers,[12] the National Lawyers Guild,[13] and the Center for Constitutional Rights.[14] The United States government does not recognize the existence of political prisoners within its borders.[15]

Legal challenge

[edit]In 1994, Muntaqim (representing himself) challenged the disenfranchisement of felons in New York in Muntaqim v. Coombe, arguing that it disproportionately impacted African Americans and therefore violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The case was first dismissed by the United States District Court for the Northern District of New York on the grounds that applying Section 2 (a federal law) to state felon-disenfranchisement law "would upset the sensitive relation between federal and state criminal jurisdiction."[16] They cited then-recent Court precedent[17] which required that laws which sought to change any balance between state and federal governments must explicitly say so in writing. In 2005 the case was argued again in front of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, which agreed to rehear the case alongside Hayden v. Pataki via internal poll. The Second Circuit ruled that due to Muntaqim being initially incarcerated in California under different charges, and only later transferred to New York where he has never voted nor had the right to vote at any time, they lacked the jurisdiction to hear the case and must dismiss.[18]

Second conviction

[edit]In 1999 the investigation into the death of San Francisco police officer John V. Young was re-opened, costing the city over $2 million but eventually leading to charges being filed against eight former BLA members in 2007, including Muntaqim.[19] Members of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, who needed to approve the $2 million appropriation for the investigation and legal fees, requested that the charges be dropped against the remaining defendants, citing the use of torture and denial of right to counsel in order to obtain confessions.[20] The SF Police Officer Association president at the time, Gary P. Delagnes, responded by stating “Regardless of how this confession was obtained, these seven people murdered a police officer in 1971.” Charges were dropped against six of the eight accused between 2008 and 2011. Muntaqim and Bell offered pleas in return for greatly reduced sentences (time served plus probation).[20][21]

Parole and release

[edit]While abolitionists and other left-wing organizations believed he should be paroled, others, mainly law enforcement, opposed his release. In 2002, former New York City mayor Mike Bloomberg publicized his opposition to granting Muntaqim parole, stating, “Anthony Bottom's crime is unforgivable, and its consequences will remain forever with the families of the police officers, as well as the men and women of the New York City Police Department.”[22] Councilman Charles Barron, a self-described Black revolutionary, is one of Muntaqim's active advocates.[23]

Muntaqim had a hearing with the parole board on November 17, 2009, and was again denied parole and remained incarcerated.[24] He was transferred from Attica Correctional Facility to Southport Correctional Facility near Elmira, New York, in early January, 2017. In June 2020, Muntaqim was reported to be under treatment in a prison hospital for Coronavirus disease. He attempted to gain release based on public health guidance advising the release of medically vulnerable people, but New York state attorney general Letitia James challenged the appeal, and the courts struck down a judge's order mandating his release.[1] Within a few months, however, the parole board finally approved him for release, and his supporters confirmed that he left prison on October 7, 2020.[2] Muntaqim was the last of the "New York Three" to leave prison. Herman Bell had already been paroled in 2018[25] and Albert “Nuh” Washington died of liver cancer in April 2000 in New York State's Coxsackie Correctional Facility.

The day after his release, Muntaqim filled out a voting registration form despite not being eligible to vote due to his felony conviction. This registration form had been provided alongside other documents given to Muntaqim as part of his release from prison and re-integration into society. Then-county GOP Chair Bill Napier alerted the Monroe County DA on the matter, deeming Muntaqim a "danger to society".[7] He was charged with two felony counts and the lesser offense of providing a false affidavit, but the grand jury in the case refused to indict him.[26]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Black, Hannah (June 1, 2020). "Jalil Muntaqim should not die in prison". The Guardian. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ a b Harrison, Ishek (4 October 2020). "Former Black Liberation Army Activist Granted Parole After 49 Years and Numerous Requests, Impending Release Sparks Backlash".

- ^ a b Gross, Daniel (January 25, 2019). "The Eleventh Parole Hearing of Jalil Abdul Muntaqim". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ a b James, Joy, ed. Imprisoned Intellectuals: America’s Political Prisoners Write on Life, Liberation and Rebellion. 1st edn. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield. 2003.

- ^ a b Muntaqim, Jalil (2002). On the Black Liberation Army. Abraham Guillen Press. ISBN 1894925130.

- ^ Black Liberation Army (1977). Black Liberation Army Study Guide + Political Dictionary. Black Liberation Army. pp. 1–47.

- ^ a b "When will atonement come for Jalil Muntaqim?". Democrat and Chronicle. 2021-03-30. Retrieved 2023-08-29.

- ^ a b Muntaqim, Jalil (2017-11-06). "Jalil A. Muntaqim: The making of a movement". San Francisco Bay View. Retrieved 2023-09-05.

- ^ "After 47 Years Behind Bars, Will Jalil Muntaqim Go Free?". Retrieved 2023-09-05.

- ^ Wolf, Paul; et al. (Robert Boyle, Bob Brown, Tom Burghardt, Noam Chomsky, Ward Churchill, Kathleen Cleaver, Bruce Ellison, Cynthia McKinney, Nkechi Taifa, Laura Whitehorn, Nicholas Wilson, and Howard Zinn.) (2001). COINTELPRO: The Untold American Story (PDF). Congressional Black Caucus. pp. 61–64.

- ^ "Millennials Are Killing Capitalism: "We Charge Genocide, Again" - Jalil Muntaqim on The Spirit of Mandela Tribunal, Political Prisoners, and a Life in Struggle". millennialsarekillingcapitalism.libsyn.com. Retrieved 2023-08-29.

- ^ National Conference of Black Lawyers (3 December 2010). "UNITED STATES POLITICAL PRISONERS/PRISONERS OF WAR" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Why the PPSC exists | National Lawyers Guild". www.nlg.org. 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2023-09-05.

- ^ "Black August - A Celebration of Freedom Fighters Past and Present". Center for Constitutional Rights. Retrieved 2023-09-05.

- ^ "Voices of Political Prisoners". United States Department of State. Retrieved 2023-09-05.

- ^ "Jalil Abdul Muntaqim, Also Known As Anthony Bottom, Plaintiff-appellant, v. Phillip Coombe, Anthony Annucci, and Louis F. Mann, Defendants-appellees, 366 F.3d 102 (2d Cir. 2004)". Justia Law. Retrieved 2023-09-05.

- ^ "Baker v. Pataki, 85 F.3d 919 | Casetext Search + Citator". casetext.com. Retrieved 2023-09-05.

- ^ "Jalil Abdul Muntaqim, A/k/a Anthony Bottom, Plaintiff-appellant, v. Phillip Coombe, Anthony Annucci, Louis F. Mann, Defendants-appellees.docket No. 01-7260-cv, 449 F.3d 371 (2d Cir. 2006)". Justia Law. Retrieved 2023-09-05.

- ^ O'Hair, Amy (28 August 2021). "50 Years On: The Ingleside Police Station Ambush and the Black Liberation Army". Sunnyside History Project.

- ^ a b "On the Unjust Prosecution of the San Francisco 8". August 27, 2009. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ 2nd guilty plea in 1971 killing of S.F. officer (via SFGate)

- ^ "Mayor Opposes Parole for Man In 1971 Killings of Two Officers".

- ^ "Adding Charm to Revolution; But Some Say Charles Barron Risks Going Too Far".

- ^ NY State Inmate locator DIN=77A4283 cut: BOTTOM

- ^ Law, Victoria (26 February 2019). "Police Unions Fight To Rescind Parole For Former Black Panther". The Appeal. The Justice Collaborative. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Andreatta, David (30 March 2021). "Grand jury refuses to indict parolee Jalil Muntaqim on voter fraud charges". Rochester City Newspaper.

External links

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]Books authored

[edit]- We Are Our Own Liberators: Selected Prison Writings. Arissa Media Group, 2nd expanded edition 2010. ISBN 978-0974288468

- Escaping the Prism.. Fade to Black: Poetry and Essays. Kersplebedeb, 2015. ISBN 978-1894946629

- 1951 births

- Activists from California

- American prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment

- American people convicted of murdering police officers

- Living people

- Members of the Black Liberation Army

- Members of the Black Panther Party

- People convicted of murder by New York (state)

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by New York (state)

- People from Oakland, California

- People paroled from life sentence